Code

library(tidyverse)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, warning=FALSE, message=FALSE)Matthew Norberg

September 17, 2022

Today’s challenge is to

Read in one (or more) of the following data sets, available in the posts/_data folder, using the correct R package and command.

Add any comments or documentation as needed. More challenging data may require additional code chunks and documentation.

Using a combination of words and results of R commands, can you provide a high level description of the data? Describe as efficiently as possible where/how the data was (likely) gathered, indicate the cases and variables (both the interpretation and any details you deem useful to the reader to fully understand your chosen data).

First, let’s look at the columns in the data set and the first few entries to get an idea of what each instance of the data is describing.

cols(

hotel = col_character(),

is_canceled = col_double(),

lead_time = col_double(),

arrival_date_year = col_double(),

arrival_date_month = col_character(),

arrival_date_week_number = col_double(),

arrival_date_day_of_month = col_double(),

stays_in_weekend_nights = col_double(),

stays_in_week_nights = col_double(),

adults = col_double(),

children = col_double(),

babies = col_double(),

meal = col_character(),

country = col_character(),

market_segment = col_character(),

distribution_channel = col_character(),

is_repeated_guest = col_double(),

previous_cancellations = col_double(),

previous_bookings_not_canceled = col_double(),

reserved_room_type = col_character(),

assigned_room_type = col_character(),

booking_changes = col_double(),

deposit_type = col_character(),

agent = col_character(),

company = col_character(),

days_in_waiting_list = col_double(),

customer_type = col_character(),

adr = col_double(),

required_car_parking_spaces = col_double(),

total_of_special_requests = col_double(),

reservation_status = col_character(),

reservation_status_date = col_date(format = "")

)# A tibble: 6 × 32

hotel is_ca…¹ lead_…² arriv…³ arriv…⁴ arriv…⁵ arriv…⁶ stays…⁷ stays…⁸ adults

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Resort… 0 342 2015 July 27 1 0 0 2

2 Resort… 0 737 2015 July 27 1 0 0 2

3 Resort… 0 7 2015 July 27 1 0 1 1

4 Resort… 0 13 2015 July 27 1 0 1 1

5 Resort… 0 14 2015 July 27 1 0 2 2

6 Resort… 0 14 2015 July 27 1 0 2 2

# … with 22 more variables: children <dbl>, babies <dbl>, meal <chr>,

# country <chr>, market_segment <chr>, distribution_channel <chr>,

# is_repeated_guest <dbl>, previous_cancellations <dbl>,

# previous_bookings_not_canceled <dbl>, reserved_room_type <chr>,

# assigned_room_type <chr>, booking_changes <dbl>, deposit_type <chr>,

# agent <chr>, company <chr>, days_in_waiting_list <dbl>,

# customer_type <chr>, adr <dbl>, required_car_parking_spaces <dbl>, …The output above shows that each row in the data set is describing an instance of a hotel booking. For each booking, we are recording 32 data parameters as described by the columns. Additionally, we can see that some of the entries have a value of “NULL”. For instance, the first row of the data set has an agent and company listed as “NULL”. This is probably used to describe instances in which an travel agent or travel company was not used. The following code creates a data frame containing all the rows that have a “NULL” value.

# A tibble: 6 × 32

hotel is_ca…¹ lead_…² arriv…³ arriv…⁴ arriv…⁵ arriv…⁶ stays…⁷ stays…⁸ adults

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Resort… 0 342 2015 July 27 1 0 0 2

2 Resort… 0 737 2015 July 27 1 0 0 2

3 Resort… 0 7 2015 July 27 1 0 1 1

4 Resort… 0 13 2015 July 27 1 0 1 1

5 Resort… 0 14 2015 July 27 1 0 2 2

6 Resort… 0 14 2015 July 27 1 0 2 2

# … with 22 more variables: children <dbl>, babies <dbl>, meal <chr>,

# country <chr>, market_segment <chr>, distribution_channel <chr>,

# is_repeated_guest <dbl>, previous_cancellations <dbl>,

# previous_bookings_not_canceled <dbl>, reserved_room_type <chr>,

# assigned_room_type <chr>, booking_changes <dbl>, deposit_type <chr>,

# agent <chr>, company <chr>, days_in_waiting_list <dbl>,

# customer_type <chr>, adr <dbl>, required_car_parking_spaces <dbl>, …The original dataframe had 119,390 rows while the new dataframe called ‘NULLS’ created above has 119,173 rows. This shows that the vast majority of the rows in the dataset have at least one “NULL” value (99.8%).

Let’s find out if there are any missing values in the data set. The code chunk below finds the columns that contain NA.

The ‘children’ column of the data set contains values that are not available. We can use the filter function to identify the rows of the data set that contain NA.

# A tibble: 4 × 32

hotel is_ca…¹ lead_…² arriv…³ arriv…⁴ arriv…⁵ arriv…⁶ stays…⁷ stays…⁸ adults

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 City H… 1 2 2015 August 32 3 1 0 2

2 City H… 1 1 2015 August 32 5 0 2 2

3 City H… 1 1 2015 August 32 5 0 2 3

4 City H… 1 8 2015 August 33 13 2 5 2

# … with 22 more variables: children <dbl>, babies <dbl>, meal <chr>,

# country <chr>, market_segment <chr>, distribution_channel <chr>,

# is_repeated_guest <dbl>, previous_cancellations <dbl>,

# previous_bookings_not_canceled <dbl>, reserved_room_type <chr>,

# assigned_room_type <chr>, booking_changes <dbl>, deposit_type <chr>,

# agent <chr>, company <chr>, days_in_waiting_list <dbl>,

# customer_type <chr>, adr <dbl>, required_car_parking_spaces <dbl>, …The data set has 119,390 rows. The code above shows that 4 of those rows contain entries that are not available. Since only a small proportion of rows contain entries that are not available, it is likely safe to remove them. Running the code cell below will remove the rows listed above and generate a clean data set.

An analysis of the ‘arrival_data_year’ column reveals that the data was collected over the course of three years from 2015 to 2017. This can be shown with the following R command: summary(df$arrival_date_year). Additionally, we can see that the tibble contains information about hotel bookings from all over the world, as evident by the ‘country’ column. The code chunk below reveals that there are 167 unique countries in the data set. Note that although the tibble generated below has 168 rows, one of those rows is for those data entries whose country is not known. In these cases, the country is listed as “NULL”.

# A tibble: 178 × 2

country TotalBookings

<chr> <int>

1 PRT 48586

2 GBR 12129

3 FRA 10415

4 ESP 8568

5 DEU 7287

6 ITA 3766

7 IRL 3375

8 BEL 2342

9 BRA 2224

10 NLD 2104

# … with 168 more rows Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

1.00 2.00 12.50 670.71 74.75 48586.00

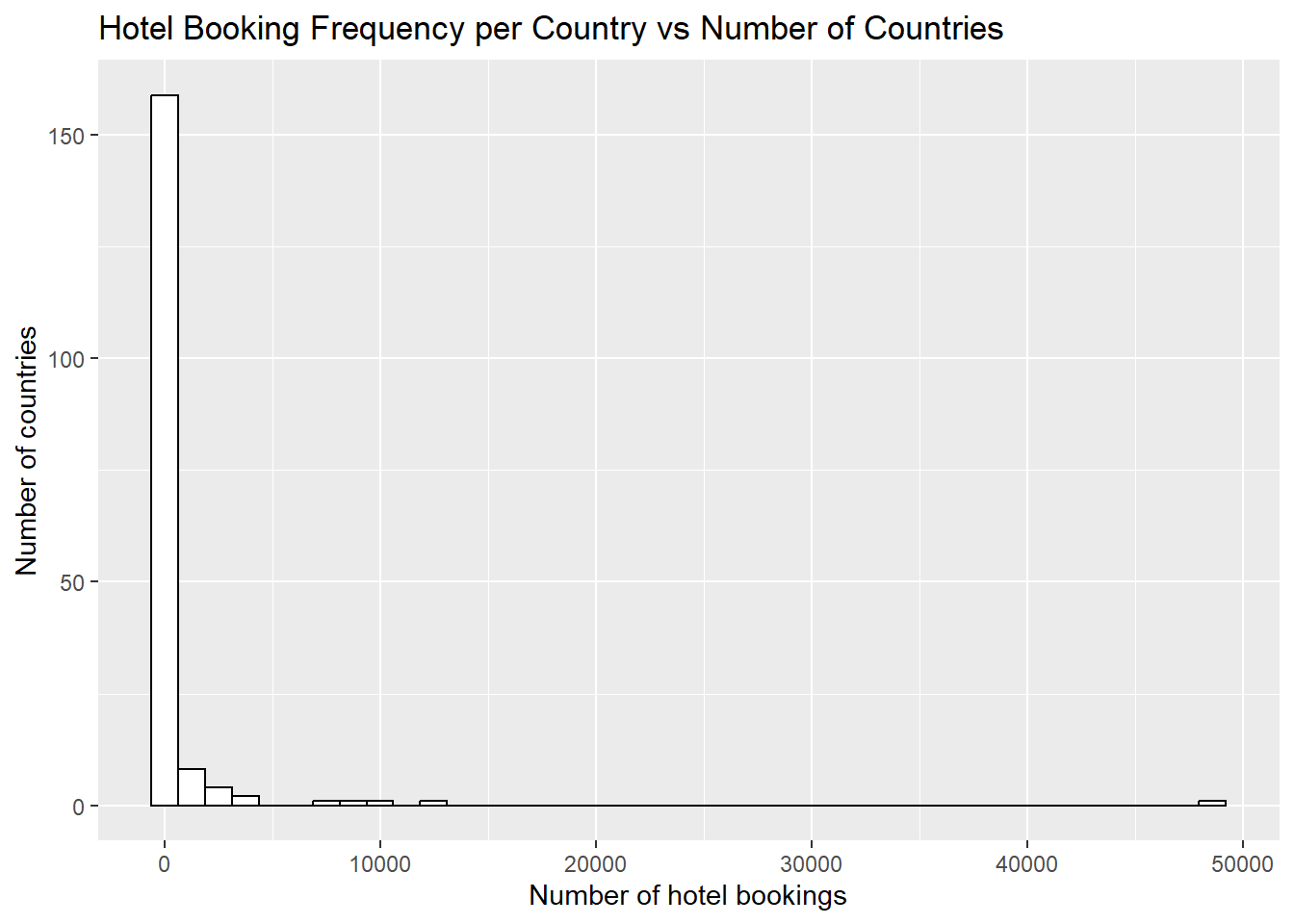

An analysis on the tibble shows that Portugal has the most hotel bookings in the data set. Additionally, the summary command below reveals that the average number of bookings is 670.71 and the median number of bookings is 12.5. The histogram derived from the count of each country further reveals that the number of bookings per country is skewed.

The categorical nature of the ‘hotel’, ‘meal’, ‘reserved_room_type’, and ‘customer_type’ columns of the data set lead me to believe that the data was collected by a singular Hotel Company that has locations all over the world. They have categorized their hotels as being in one of two possible categories, “Resort Hotel” and “City Hotel”. It seems unlikely that multiple hotel companies would use the same categorization. Additionally, this particular hotel company has a set of meal categories, room type categories, and customer categories. I would argue that these categorization are not a standard that is being used by multiple hotels which furthers my theory that this data was collected by a singular hotel company. The code chunk below lists the possible categories for each of the aforementioned columns.

Conduct some exploratory data analysis, using dplyr commands such as group_by(), select(), filter(), and summarise(). Find the central tendency (mean, median, mode) and dispersion (standard deviation, mix/max/quantile) for different subgroups within the data set.

Let’s look at the set of hotel bookings that took place in the United States. I was interested in determining how many bookings were made in which the customer got the type of room that they requested. The code chunk below answers this question.

# Get the rows that contain hotel booking information in the United States

us <- filter(df, country == "USA")

# Find the proportion of bookings where the customer got the correct room type

correctType <- us %>%

filter(reserved_room_type == assigned_room_type) %>%

summarise(Count = n()) / dim(us)[1]

# Display the answer

cat("The proportion of bookings where the customer got the correct room type in the United States:", correctType[[1]])The proportion of bookings where the customer got the correct room type in the United States: 0.8874583The data shows that most people were able to get the room type that they requested in the United States. However, I was in interested in figuring out how the United States compares to other countries in terms of accuracy of hotel bookings. The following code chunk computes the booking accuracy of all countries listed in the table and sorts them based on accuracy.

# Compute the booking accuracy of each country

r <- df %>%

group_by(country) %>%

filter(reserved_room_type == assigned_room_type) %>%

summarise(CorrectRoom = n()) %>%

left_join(countries, by = "country") %>%

mutate(PercentCorrect = CorrectRoom / TotalBookings) %>%

arrange(desc(PercentCorrect))

# Display the results

head(r)# A tibble: 6 × 4

country CorrectRoom TotalBookings PercentCorrect

<chr> <int> <int> <dbl>

1 AIA 1 1 1

2 ALB 12 12 1

3 AND 7 7 1

4 ARM 8 8 1

5 ASM 1 1 1

6 ATA 2 2 1 country CorrectRoom TotalBookings PercentCorrect

Length:173 Min. : 1.0 Min. : 1.0 Min. :0.3333

Class :character 1st Qu.: 2.0 1st Qu.: 3.0 1st Qu.:0.8765

Mode :character Median : 14.0 Median : 14.0 Median :0.9231

Mean : 603.9 Mean : 690.1 Mean :0.9107

3rd Qu.: 67.0 3rd Qu.: 80.0 3rd Qu.:1.0000

Max. :42477.0 Max. :48586.0 Max. :1.0000 The results from the code chunk above show that there are many countries with perfect booking accuracy. Furthermore, the average accuracy was 91%. Therefore, the United States is below average in terms of hotel booking accuracy.

In addition to hotel booking accuracy, I was also interested in the total number of nights stayed that each booking incurred in the United States. The data set has two columns for the number of nights stayed: ‘stays_in_weekend_nights’ and ‘stays_in_week_nights’. Here, I am defining the total number of nights to be the sum of those two children. Specifically, I wanted to know if the total number of nights stayed in the hotel is influenced by whether or not the booking included children and babies. The code chunk below computes the average number of nights and the median number of nights for each (children, babies) pairing in the data set for hotel bookings in the US.

# Compute central tendency and dispersion for total number of nights in the united states grouped by children and babies

# Total number of nights = weekend nights + week nights

temp <- us %>%

mutate(total_nights = stays_in_weekend_nights + stays_in_week_nights) %>%

group_by(children, babies) %>%

summarise(AverageNights = mean(total_nights), NumOccurences = n(), MedianNights = median(total_nights))

# Display the information

temp# A tibble: 5 × 5

# Groups: children [4]

children babies AverageNights NumOccurences MedianNights

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl>

1 0 0 2.76 1871 2

2 0 1 3.17 6 3.5

3 1 0 2.51 83 2

4 2 0 3.16 132 3

5 3 0 1.6 5 1 The results in the table above show that offspring status of a hotel booking does not seem to have an impact on the average number of nights stayed in the hotel.

Lastly, I was interested in the lead time attribute for bookings in the United States. I wanted to determine if some months are more popular than others and therefore have a larger lead time. The following code chunk computes averaged lead time grouped by ‘arrival_date_month’ to determine which months are the most popular.

# A tibble: 12 × 5

arrival_date_month AverageLeadTime sdLeadTime maxLeadTime minLeadTime

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 April 76.5 74.2 317 0

2 August 101. 104. 504 0

3 December 58.7 63.3 237 0

4 February 24.9 35.8 240 0

5 January 35.3 47.3 343 0

6 July 104. 96.4 476 0

7 June 89.0 77.0 423 0

8 March 54.3 56.6 286 0

9 May 85.2 80.8 340 0

10 November 48.4 51.4 260 0

11 October 67.4 78.6 241 0

12 September 56.6 73.5 542 0The results above show that the summer months seem to have the highest average lead time while some of the winter months have the fewest lead times. This may indicate that the summer months are the most popular times to go on vacation.

Be sure to explain why you choose a specific group. Comment on the interpretation of any interesting differences between groups that you uncover. This section can be integrated with the exploratory data analysis, just be sure it is included.

I choose to look at hotel bookings in the United States to do my analysis. The first portion of my analysis looked at hotel booking accuracy in the United States versus the other countries in the data set. I was surprised that the United States is below the average accuracy in the data set.

I also looked at the total number of nights for each booking the United States. I wanted to know if having children or babies included in the hotel booking impacted how long people stay. The idea was interesting, but the results indicated that having children and babies included in the booking did not seem to impact total stay.

Lastly, I looked at the amount of lead time in hotel bookings for the United States in order to see which months were the most popular. Unsurprisingly, the summer months were among the most popular and the least popular were winter months.

---

title: "Challenge 2 Instructions"

author: "Matthew Norberg"

desription: "Data wrangling: using group() and summarise()"

date: "09/17/2022"

format:

html:

toc: true

code-fold: true

code-copy: true

code-tools: true

categories:

- challenge_2

- railroads

- faostat

- hotel_bookings

---

```{r}

#| label: setup

#| warning: false

#| message: false

library(tidyverse)

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, warning=FALSE, message=FALSE)

```

## Challenge Overview

Today's challenge is to

1) read in a data set, and describe the data using both words and any supporting information (e.g., tables, etc)

2) provide summary statistics for different interesting groups within the data, and interpret those statistics

## Read in the Data

Read in one (or more) of the following data sets, available in the `posts/_data` folder, using the correct R package and command.

- railroad\*.csv or StateCounty2012.xls ⭐

- FAOstat\*.csv or birds.csv ⭐⭐⭐

- hotel_bookings.csv ⭐⭐⭐⭐

```{r}

# Read in the hotel bookings data set

df <- read_csv('./_data/hotel_bookings.csv')

```

Add any comments or documentation as needed. More challenging data may require additional code chunks and documentation.

## Describe the data

Using a combination of words and results of R commands, can you provide a high level description of the data? Describe as efficiently as possible where/how the data was (likely) gathered, indicate the cases and variables (both the interpretation and any details you deem useful to the reader to fully understand your chosen data).

First, let's look at the columns in the data set and the first few entries to get an idea of what each instance of the data is describing.

```{r}

spec(df)

head(df)

```

The output above shows that each row in the data set is describing an instance of a hotel booking. For each booking, we are recording 32 data parameters as described by the columns. Additionally, we can see that some of the entries have a value of "NULL". For instance, the first row of the data set has an agent and company listed as "NULL". This is probably used to describe instances in which an travel agent or travel company was not used. The following code creates a data frame containing all the rows that have a "NULL" value.

```{r}

NULLS <- df %>% filter_all(any_vars(. %in% c('NULL')))

head(NULLS)

```

The original dataframe had 119,390 rows while the new dataframe called 'NULLS' created above has 119,173 rows. This shows that the vast majority of the rows in the dataset have at least one "NULL" value (99.8%).

Let's find out if there are any missing values in the data set. The code chunk below finds the columns that contain NA.

```{r}

# Identify columns containing NA

colnames(df)[apply(df, 2, anyNA)]

```

The 'children' column of the data set contains values that are not available. We can use the filter function to identify the rows of the data set that contain NA.

```{r}

# Find the rows in the data set containing NA

filter(df, is.na(children))

```

The data set has 119,390 rows. The code above shows that 4 of those rows contain entries that are not available. Since only a small proportion of rows contain entries that are not available, it is likely safe to remove them. Running the code cell below will remove the rows listed above and generate a clean data set.

```{r}

df <- na.omit(df)

```

An analysis of the 'arrival_data_year' column reveals that the data was collected over the course of three years from 2015 to 2017. This can be shown with the following R command: `summary(df$arrival_date_year)`. Additionally, we can see that the tibble contains information about hotel bookings from all over the world, as evident by the 'country' column. The code chunk below reveals that there are 167 unique countries in the data set. Note that although the tibble generated below has 168 rows, one of those rows is for those data entries whose country is not known. In these cases, the country is listed as "NULL".

```{r}

countries <- select(df, country) %>%

group_by(country) %>%

summarise(TotalBookings = n()) %>%

arrange(desc(TotalBookings))

countries

summary(countries$TotalBookings)

countryHist <- ggplot(countries, aes(x=TotalBookings)) + geom_histogram(colour = "black", fill = "white", bins = 40)

print(countryHist + ggtitle("Hotel Booking Frequency per Country vs Number of Countries") +

labs(x = "Number of hotel bookings", y = "Number of countries"))

```

An analysis on the tibble shows that Portugal has the most hotel bookings in the data set. Additionally, the summary command below reveals that the average number of bookings is 670.71 and the median number of bookings is 12.5. The histogram derived from the count of each country further reveals that the number of bookings per country is skewed.

The categorical nature of the 'hotel', 'meal', 'reserved_room_type', and 'customer_type' columns of the data set lead me to believe that the data was collected by a singular Hotel Company that has locations all over the world. They have categorized their hotels as being in one of two possible categories, "Resort Hotel" and "City Hotel". It seems unlikely that multiple hotel companies would use the same categorization. Additionally, this particular hotel company has a set of meal categories, room type categories, and customer categories. I would argue that these categorization are not a standard that is being used by multiple hotels which furthers my theory that this data was collected by a singular hotel company. The code chunk below lists the possible categories for each of the aforementioned columns.

```{r}

unique(df$hotel)

unique(df$reserved_room_type)

unique(df$is_repeated_guest)

```

## Provide Grouped Summary Statistics

Conduct some exploratory data analysis, using dplyr commands such as `group_by()`, `select()`, `filter()`, and `summarise()`. Find the central tendency (mean, median, mode) and dispersion (standard deviation, mix/max/quantile) for different subgroups within the data set.

Let's look at the set of hotel bookings that took place in the United States. I was interested in determining how many bookings were made in which the customer got the type of room that they requested. The code chunk below answers this question.

```{r}

# Get the rows that contain hotel booking information in the United States

us <- filter(df, country == "USA")

# Find the proportion of bookings where the customer got the correct room type

correctType <- us %>%

filter(reserved_room_type == assigned_room_type) %>%

summarise(Count = n()) / dim(us)[1]

# Display the answer

cat("The proportion of bookings where the customer got the correct room type in the United States:", correctType[[1]])

```

The data shows that most people were able to get the room type that they requested in the United States. However, I was in interested in figuring out how the United States compares to other countries in terms of accuracy of hotel bookings. The following code chunk computes the booking accuracy of all countries listed in the table and sorts them based on accuracy.

```{r}

# Compute the booking accuracy of each country

r <- df %>%

group_by(country) %>%

filter(reserved_room_type == assigned_room_type) %>%

summarise(CorrectRoom = n()) %>%

left_join(countries, by = "country") %>%

mutate(PercentCorrect = CorrectRoom / TotalBookings) %>%

arrange(desc(PercentCorrect))

# Display the results

head(r)

summary(r)

```

The results from the code chunk above show that there are many countries with perfect booking accuracy. Furthermore, the average accuracy was 91%. Therefore, the United States is below average in terms of hotel booking accuracy.

In addition to hotel booking accuracy, I was also interested in the total number of nights stayed that each booking incurred in the United States. The data set has two columns for the number of nights stayed: 'stays_in_weekend_nights' and 'stays_in_week_nights'. Here, I am defining the total number of nights to be the sum of those two children. Specifically, I wanted to know if the total number of nights stayed in the hotel is influenced by whether or not the booking included children and babies. The code chunk below computes the average number of nights and the median number of nights for each (children, babies) pairing in the data set for hotel bookings in the US.

```{r}

# Compute central tendency and dispersion for total number of nights in the united states grouped by children and babies

# Total number of nights = weekend nights + week nights

temp <- us %>%

mutate(total_nights = stays_in_weekend_nights + stays_in_week_nights) %>%

group_by(children, babies) %>%

summarise(AverageNights = mean(total_nights), NumOccurences = n(), MedianNights = median(total_nights))

# Display the information

temp

```

The results in the table above show that offspring status of a hotel booking does not seem to have an impact on the average number of nights stayed in the hotel.

Lastly, I was interested in the lead time attribute for bookings in the United States. I wanted to determine if some months are more popular than others and therefore have a larger lead time. The following code chunk computes averaged lead time grouped by 'arrival_date_month' to determine which months are the most popular.

```{r}

# Lets look at lead time statistics grouped by month to see if some months are more popular

leadTime <- us %>%

group_by(arrival_date_month) %>%

summarise(AverageLeadTime = mean(lead_time),

sdLeadTime = sd(lead_time),

maxLeadTime = max(lead_time),

minLeadTime = min(lead_time))

leadTime

```

The results above show that the summer months seem to have the highest average lead time while some of the winter months have the fewest lead times. This may indicate that the summer months are the most popular times to go on vacation.

### Explain and Interpret

Be sure to explain why you choose a specific group. Comment on the interpretation of any interesting differences between groups that you uncover. This section can be integrated with the exploratory data analysis, just be sure it is included.

I choose to look at hotel bookings in the United States to do my analysis. The first portion of my analysis looked at hotel booking accuracy in the United States versus the other countries in the data set. I was surprised that the United States is below the average accuracy in the data set.

I also looked at the total number of nights for each booking the United States. I wanted to know if having children or babies included in the hotel booking impacted how long people stay. The idea was interesting, but the results indicated that having children and babies included in the booking did not seem to impact total stay.

Lastly, I looked at the amount of lead time in hotel bookings for the United States in order to see which months were the most popular. Unsurprisingly, the summer months were among the most popular and the least popular were winter months.